The Docklands Light Railway is a curious legacy of the Thatcher period, when London Docklands was designated as an Enterprise Zone. These Zones were a brainchild of planning minister Michael Heseltine and offered planning and tax concessions.

The DLR opened as a Y-shaped route from Tower Hill to Island Gardens, at the north end of Greenwich foot tunnel, and to Stratford, mostly on long-closed railway alignments. Extensions were built first to the Bank, giving it an interchange to the London underground system, and then to Lewisham on the south side of the river, to Beckton to the east and to Woolwich, again on the south side of the Thames. The Lewisham extension was expensive for what it was, involving a long viaduct, diversion of the river Ravensbourne, and burrowing under the railway embankments at Lewisham, to a terminus on the wrong side of a busy roundabout separating it from the main town centre.

Standard overhead electrification was not used, for aesthetic reasons, and an unusual system of bottom-contact third rail electrification was used instead. The trains were fairly conventional lightweight tramway-type vehicles. Driving was automatic ie from the control centre, and the member of staff acted as a general order-keeper and driver in emergency.

The system quickly proved inadequate. The fleet has been replaced three times. Trains have had to be lengthened and stations rebuilt to accommodate them. The system was never going to have the capacity to serve the commercial development at Canary Wharf, and eventually, with a contribution from developers Reichmann, the Jubilee Line Extension was constructed from Bond Street to Stratford, giving through services to Stanmore in north London. One that was open, the development of Canary Wharf could go ahead.

The system gives the impression of being clean and well run and obviously serves a useful function. Whether it is the system that would have been built had it been planned from the start is another question. Due to the larger size of the trains, the tunneling - and there has been quite a mileage built over the years - was considerably more expensive than if some of the line had been built as a tube. Other parts of the route would, more logically, have been developed as conventional railways run with conventional stock, and eventually integrated into London Overground. Other parts again - perhaps the Lewisham route - would probably have been more useful if they had been constructed as conventional on-street tramway, which could then have gone on to Catford and Bromley and perhaps eventually have joined up with Croydon Tramlink. The Jubilee Line Extension would probably have taken a different form if the DLR had opened as a direct tube line from the Bank to Canary Wharf and Stratford. Such a route would also have been more easily extended westwards from Bank, an enhancement which remains on the list of aspirations for the DLR.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing, but already in the early 1980s planning was out of favour in the political right, especially longer-term planning. There was a desire to spend as little as possible at the start. The system, whilst quite good in its own right, is almost certainly not what would have been built if it had been planned from the outset, nor can it have been particularly good value for the money it has cost.

11 Apr 2013

8 Apr 2013

Were the standards a waste of money?

An article in this month's Steam Railway discusses the standard fleet of British Railways steam locomotives built to new designs between 1951 and 1960. There were 999 of them, and all were out of service by 1968, so they were not good value for money. Were British Railways' engineers to blame?

The story is long forgotten, but, as the article reminds us, the British Transport Commission had a sudden change of plan in the mid-1950s and diesel locomotive types which were on order in small numbers for comparative trials were ordered in large numbers before the test locomotives had even been delivered. This change of plan was imposed on the horrified engineers. Whole fleets of the diesel locomotives were effectively prototypes and the engineers were saddled with the task of resolving the teething troubles. In the case of some of the classes, the teething troubles were never resolved and the expensive hardware - typically costing five times as much as the equivalent steam locomotives - went to the scrapyard even faster than the "Standards".

Thus, all the planning that had been done to supersede steam traction in an orderly way was set aside and dieselisation was conducted in a rush. In France and West Germany, steam remained in use for another ten years or so.

The article suggests that had economic considerations applied, the locomotives would have continued in service until the early 1990s, as intended. What the article does not mention in the article is that, as information has come to light both through research, release of documents and experience of the locomotives in preservation, they were exceptionally well-designed both overall and in detail, being almost free of inherent flaws. The 8P Duke of Gloucester and the 9F 2-10-0 were an outstandingly good designs. They would have had particularly long service lives.

They would then have retro-fitted with the technical improvements developed by Porta, Wardale and Waller, that took place from the mid-1970. In that case they would probably still be in service on secondary routes currently operated by Sprinters and Pacers, as well as on infrastructure trains where long periods are spent doing nothing at all. In fact, it is not impossible that additional locomotives would have been built to replace the original standards as they wore out.

That said, 12 different types was undoubtedly too many. Was there really a need for the 8P Duke, and the Britannia, and the Clan class and the class 5? Or for the class 3 tender and tank engines in-between the class 4 4-6-0 and 2-6-0 types, and 2-6-4 tank, and the class 2 2-6-0 tender locomotive and the 2-6-2 tank.

It is good to see this deplorable series of events brought to attention. It is an excellent illustration of the expensive damage that can be done through political interference.

The story is long forgotten, but, as the article reminds us, the British Transport Commission had a sudden change of plan in the mid-1950s and diesel locomotive types which were on order in small numbers for comparative trials were ordered in large numbers before the test locomotives had even been delivered. This change of plan was imposed on the horrified engineers. Whole fleets of the diesel locomotives were effectively prototypes and the engineers were saddled with the task of resolving the teething troubles. In the case of some of the classes, the teething troubles were never resolved and the expensive hardware - typically costing five times as much as the equivalent steam locomotives - went to the scrapyard even faster than the "Standards".

Thus, all the planning that had been done to supersede steam traction in an orderly way was set aside and dieselisation was conducted in a rush. In France and West Germany, steam remained in use for another ten years or so.

The article suggests that had economic considerations applied, the locomotives would have continued in service until the early 1990s, as intended. What the article does not mention in the article is that, as information has come to light both through research, release of documents and experience of the locomotives in preservation, they were exceptionally well-designed both overall and in detail, being almost free of inherent flaws. The 8P Duke of Gloucester and the 9F 2-10-0 were an outstandingly good designs. They would have had particularly long service lives.

They would then have retro-fitted with the technical improvements developed by Porta, Wardale and Waller, that took place from the mid-1970. In that case they would probably still be in service on secondary routes currently operated by Sprinters and Pacers, as well as on infrastructure trains where long periods are spent doing nothing at all. In fact, it is not impossible that additional locomotives would have been built to replace the original standards as they wore out.

That said, 12 different types was undoubtedly too many. Was there really a need for the 8P Duke, and the Britannia, and the Clan class and the class 5? Or for the class 3 tender and tank engines in-between the class 4 4-6-0 and 2-6-0 types, and 2-6-4 tank, and the class 2 2-6-0 tender locomotive and the 2-6-2 tank.

It is good to see this deplorable series of events brought to attention. It is an excellent illustration of the expensive damage that can be done through political interference.

6 Apr 2013

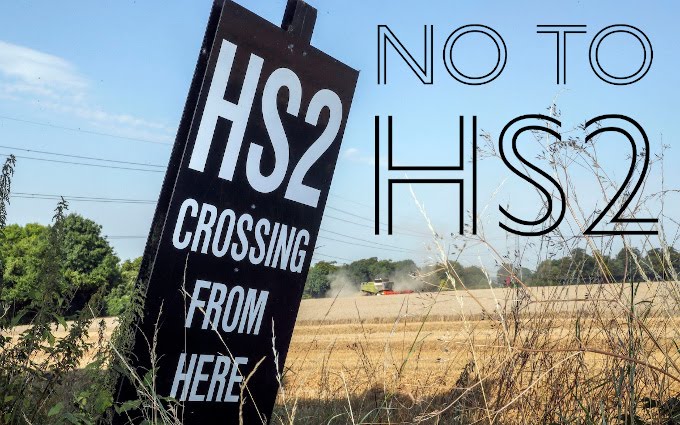

How the real case against HS2 has been buried

The economic case against HS2 has scarcely featured in public debate, which has mostly focussed on the harm it will do to well-heeled residents in Chiltern villages. One explanation is now surfacing. A lobbying

firm employed by the government to promote the case for the High Speed 2

railway line is at the centre of a row after its founder, a

Tory-supporting peer, was accused of painting opponents of the scheme as

posh nimbys worried about their hunting rights.

Read more in this Guardian article here.

Read more in this Guardian article here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)